For many, the allure of Thailand as a retirement haven is undeniable. From its vibrant culture and warm climate to its significantly lower cost of living compared to Western nations, the Kingdom offers an appealing prospect for those seeking a tranquil yet engaging post-career life. However, transitioning from a vacation mindset to a long-term residency, particularly when it involves significant financial investment like property acquisition, demands a meticulous, data-backed approach. This article is designed to be your discerning companion, equipping you with the insights needed to navigate the intricacies of purchasing a retirement home in Thailand effectively and securely.

We will delve into the legal frameworks, explore viable ownership structures, and outline the precise procedures, ensuring you approach this significant investment with confidence and clarity.

Understanding the Legal Landscape: Land vs. Condo Ownership

The fundamental distinction in Thai property law, especially for foreign nationals, lies between owning land and owning a condominium unit. This is the cornerstone of your property search and demands a clear understanding from the outset. As a general principle, non-Thai individuals or entities are prohibited from owning land in Thailand. This protectionist measure, enshrined in the Land Code Act B.E. 2497, aims to preserve national sovereignty over its natural resources.

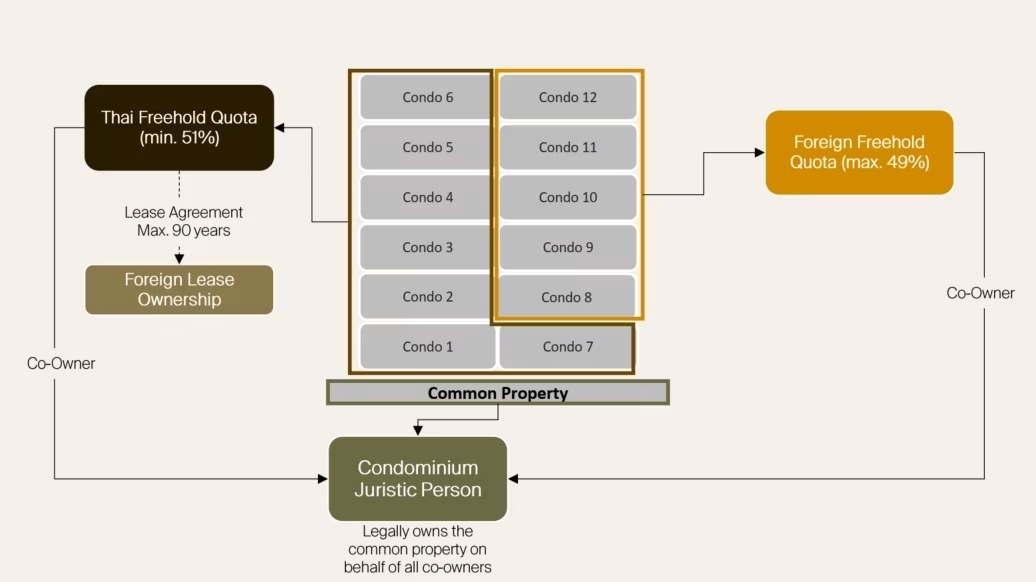

However, while direct land ownership is restricted, the purchase of condominium units is explicitly permitted under the Condominium Act B.E. 2522 (1979), with specific stipulations. A foreign national can directly own a condominium unit in their name, provided that the total area of the units owned by foreigners in a particular condominium building does not exceed 49% of the total saleable area of all units in that building. This 49% quota is a critical piece of data that developers and real estate agents must adhere to, and it’s something you must verify before committing to a purchase. Properties in popular expat hubs like Phuket, Pattaya, or specific areas of Bangkok often reach this foreign quota quickly, making it essential to act decisively once a suitable unit is identified.

For anything that involves land – be it a standalone house, a villa with a garden, or an undeveloped plot – direct foreign ownership is generally not allowed. This fact often surprises first-time buyers, leading to misunderstandings. However, it does not mean that foreigners cannot control and benefit from land use in Thailand; it simply means the legal mechanisms differ significantly from direct freehold ownership.

Buying a Condominium

Buying a condominium unit in Thailand is the most straightforward path for foreign individuals seeking direct ownership. As mentioned, the 49% foreign quota is the primary legal hurdle. When considering a condo, always ask for documentation confirming the remaining foreign quota. Reputable developers or agencies will readily provide this. Here are the primary strategies for a direct condo purchase:

1. Direct Freehold Ownership (within 49% Quota)

This is the simplest and most recommended method for foreign individuals. You purchase the unit outright, receiving a title deed (Chanote) in your name, which grants you full ownership of the unit. The funds for the purchase must be remitted from overseas in foreign currency and converted into Thai Baht in Thailand. The Thai bank issuing the Foreign Exchange Transaction Form (FETF) or credit note (formerly a document called TT3 or Thor Tor 3) is a crucial record for proving the foreign origin of funds, which is required by the Land Department for the transfer of ownership. This process ensures transparency and compliance with Thai regulations.

2. Leasehold Ownership for Condos (less common but possible)

While less common for condos due to the availability of freehold, it is possible to acquire a condominium unit on a leasehold basis. This means you enter into a long-term lease agreement, typically for 30 years, with the option to renew for two additional 30-year terms (totaling 90 years). You do not own the unit outright, but you have the exclusive right to use and occupy it for the lease duration. This option might be considered if the freehold foreign quota is exhausted in a desirable building or if a developer offers specific leasehold incentives.

Acquiring a House or Land

As direct foreign ownership of land is generally prohibited, acquiring a house or land requires more intricate legal structures. These methods come with varying degrees of complexity, risk, and control. Global Property Guide’s data indicates that while foreign investment in Thai property is robust, navigating the legal framework is paramount for secure transactions.

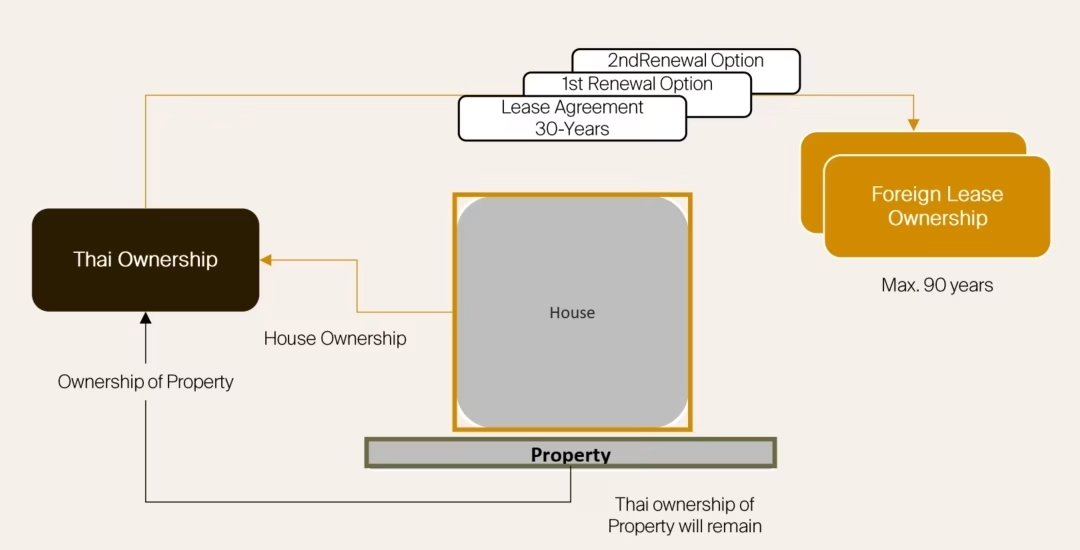

1. Leasehold Ownership (for Land/Houses)

This is the most common and safest method for foreigners to control land and the house built upon it. You enter into a registered lease agreement with a Thai landowner for a maximum term of 30 years, with the possibility of renewal for two consecutive 30-year terms, effectively granting you control for up to 90 years. The lease agreement is registered with the Land Department, providing a strong legal foundation. While you do not own the land itself, you own the structures (house) built on it, and you have exclusive rights to use and benefit from the land for the lease duration. It’s crucial that the lease agreement is meticulously drafted by a lawyer to ensure clauses for renewal are enforceable and to protect your interests in the event of the landowner’s death or sale of the land. According to a Bangkok Post article, leasehold structures are increasingly popular for foreigners investing in villas and houses, especially in tourist areas.

2. Setting Up a Thai Company (Holding Company)

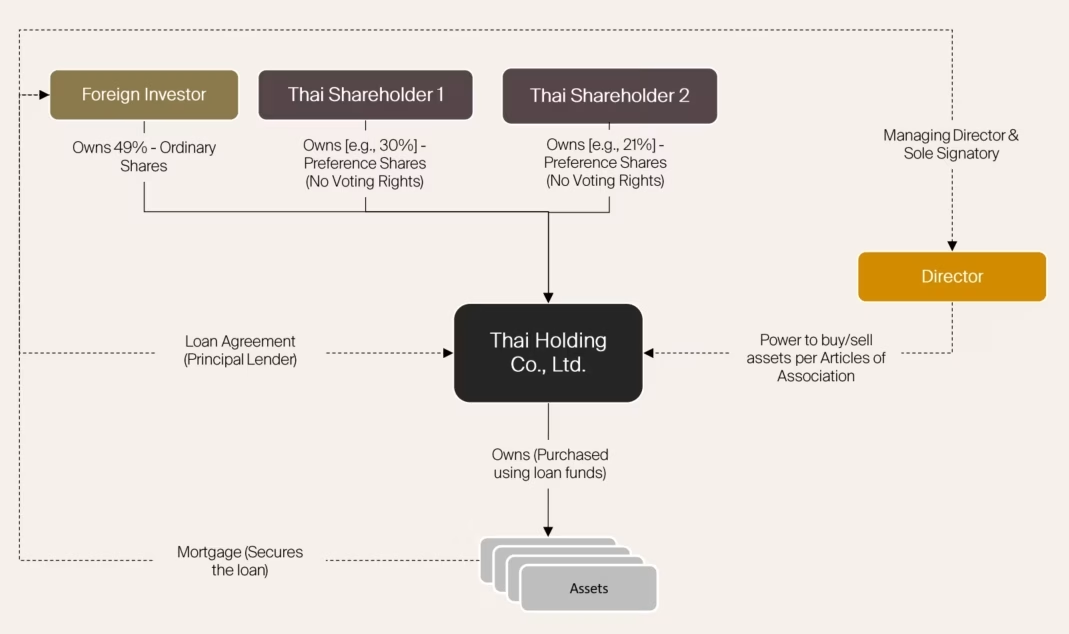

A sophisticated and common strategy for foreign nationals to exercise control over land and property in Thailand is by establishing a Thai Limited Company. This entity is legally permitted to own land, and while a foreigner can be a director with full operational control, Thai law mandates that at least 51% of the company’s shares must be held by Thai nationals. The strategy is built on three pillars of control that work in unison: Directorship, Share Structure, and Financial Leverage.

The success of this strategy is built on three pillars of control that work in unison: Absolute Directorial Authority, Engineered Shareholder Power, and Secured Financial Leverage.

Absolute Directorial Authority

The primary foundation of control is not derived from share ownership, but from embedding ultimate power in the executive role. The foreign national is appointed as the sole Managing Director, making this position the singular center of power within the company.

The instrument for achieving this is the company’s constitution, or its Articles of Association. This is the single most critical document in the entire structure and must be custom-drafted by a legal expert. The Articles grant the Managing Director exclusive and absolute power to act on behalf of the company without requiring any board or shareholder approval for key actions. Specifically, the Articles legally empower the Managing Director as the sole authority to buy, sell, lease, and mortgage all company assets, including the land itself. Furthermore, this individual is designated as the sole signatory on all company bank accounts, contracts, and legal documents, ensuring all financial and operational decisions rest with them.

Shareholder Power

The second pillar addresses the 51:49 ownership rule, legally navigating it to concentrate 100% of the voting power in the hands of the foreigner. This is achieved by dividing the company’s shares into two distinct classes with different rights.

- The foreigner’s 49% stake is comprised of Ordinary Shares. These are the only shares in the company that carry voting rights, typically on a one-share, one-vote basis.

- Conversely, the Thai nationals’ 51% majority stake is comprised of Preference Shares (known in Thai as Ahurimassit). These shares are legally structured to have limited or no voting rights on critical company decisions, such as the appointment of directors or the disposition of assets. Their primary entitlement is financial, a right to a fixed, preferred dividend before any dividends are paid to ordinary shareholders. This effectively positions the Thai partners as passive investors with a financial interest, while separating them from operational control.

Financial Leverage

Instead of injecting all funds as company capital, the foreigner provides the majority of the money needed to purchase the property as a formal personal loan to the company.

This strategy achieves two goals simultaneously. First, it establishes the foreigner as the company’s primary creditor, meaning the company has a legally binding debt obligation to them. Second, and most critically, this loan is secured by registering a mortgage over the property in the foreigner’s personal name. In the event of any internal dispute or unforeseen issue with the company, the foreigner has a direct, legally enforceable claim on the asset itself to recover their funds, providing a powerful fallback position that makes their financial control undeniable.

To support this entire structure and ensure its legal defensibility, the company must be a real, functioning business, not a passive shell. This involves several non-negotiable elements. The company must have a minimum registered capital of 2 Million THB, which must be fully paid up. It must have clear commercial objectives stated in its registration beyond simply holding property, such as property rental, business consulting, or another active service.

3. Usufruct or Superficies Agreements

These are lesser-known but viable options for specific scenarios:

- Usufruct (Sittiphan Kin Sap): Grants the right to use or occupy another person’s property and derive benefits from it for a specified period (up to 30 years) or for the lifetime of the usufructuary. This can be registered on the Chanote. It’s often used when a foreign individual wants to ensure lifetime use of a property owned by a Thai spouse or family member.

- Superficies (Sittiphan Nuea Peun Din): Grants the right to own buildings, structures, or plantations on another person’s land. This means you own the house, but not the land it sits on. This right can be granted for a specific period or for the life of the superficiary. Like a usufruct, it can be registered on the Chanote, offering strong legal protection.

These options provide more limited control than leasehold or company ownership but can be suitable depending on individual circumstances and relationships.

4. Marriage with a Thai National

If you are married to a Thai national, your spouse, as a Thai citizen, can legally purchase and own land and property in their name. However, it’s crucial to understand that the property will be solely in their name, not jointly owned by you. To protect your investment, your Thai spouse must sign a declaration at the Land Department stating that the funds used for the purchase belong to you (the foreign spouse). Additionally, a usufruct agreement can be registered, granting you the right to live in and benefit from the property for life. While this offers a degree of protection, it’s important to be aware of the inherent risks associated with relationship dissolution and potential disputes over assets, making clear legal agreements essential.

In any of these complex scenarios, the counsel of a seasoned Thai property lawyer is not merely advisable but mandatory. They can structure agreements that protect your interests within the bounds of Thai law. Don’t be tempted by informal or ‘under-the-table’ arrangements, as these carry significant legal risks and can lead to financial losses.

The Procedure of Buying a House (or Condo)

The process, while varying slightly depending on whether it’s a condo or a land-based property via leasehold/company, generally follows these stages. This is a high-level overview, and each step requires legal supervision.

| Step 1: Property Search and Selection |

| Identify properties that meet your criteria and fit within the legal ownership structures available to you. This involves extensive research, viewings, and initial discussions with sellers or agents. |

| Step 2: Due Diligence |

Once you’ve found a suitable property, this is the most critical phase. Engage an independent Thai property lawyer to conduct thorough due diligence. This includes:

|

| Step 3: Offer and Deposit |

| Once due diligence is satisfactory, you’ll make an offer to the seller. If accepted, a Reservation Agreement or Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) is signed, and a deposit (typically 5-10% of the purchase price) is paid. This deposit is usually non-refundable if you back out without cause, so ensure due diligence is completed *before* this step, or include clauses for refund if issues arise. |

| Step 4: Sales and Purchase Agreement (SPA) |

Your lawyer will draft or review the SPA. This legally binding document outlines all terms and conditions of the sale, including:

For leasehold agreements, the lease terms, renewal clauses, and registration details are meticulously included. For company purchases, the SPA would be between the seller and your newly established Thai company. |

| Step 5: Fund Remittance and FETF |

| For condo purchases, the full purchase price must be remitted from abroad in foreign currency. Instruct your bank to send the funds clearly stating the purpose as “purchase of condominium unit in Thailand” and ensure your name is on the transfer. The receiving Thai bank will issue a Foreign Exchange Transaction Form (FETF) or credit note, which is essential for registering the ownership with the Land Department. Without this, the transfer cannot proceed for freehold condo ownership. |

| Step 6: Transfer of Ownership at the Land Department |

| On the agreed transfer date, you (or your legal representative), the seller, and their representatives will meet at the local Land Department office. All required documents will be presented, including the FETF (for condos), passports, company documents (if applicable), and the SPA. Transfer fees and stamp duties are paid (these typically range from 2% to 6.3% of the appraised value or registered sale price, depending on factors like ownership duration and type of property, and are often split between buyer and seller, though this is negotiable). Once all documents are verified and fees paid, the Land Department official will register the transfer of ownership (or the leasehold/superficies agreement) and issue the new title deed in your name (or your company’s name, or register the lease/usufruct). This is the moment you officially take possession. |

As Suze Orman, the financial guru, advises, “Do not confuse what you own with who you are.” While owning a home in Thailand can be fulfilling, remember that the legal and financial commitment is substantial, and therefore, every step must be approached with informed caution and professional guidance.

Your Path to a Thai Retirement Home

Purchasing a retirement home in Thailand is a significant life decision that offers immense rewards, from cultural immersion to a relaxed lifestyle. However, it is not a decision to be taken lightly or without thorough preparation. The Thai property market, while accessible, is governed by specific laws that differ significantly from many Western jurisdictions. Your success hinges on a data-backed approach, meticulous due diligence, and the indispensable guidance of independent legal professionals.

Remember these key takeaways: direct land ownership is restricted for foreigners, making freehold condominium ownership or long-term leasehold agreements the most viable and secure paths. If a house is your goal, explore registered leasehold agreements or a properly structured, legitimate Thai company. Always verify the foreign quota for condos, meticulously vet any property, and never proceed without comprehensive legal due diligence from an independent Thai lawyer. Adhering to your ongoing tax and common area fee obligations, as well as maintaining your visa status, ensures a smooth and enjoyable retirement in the Land of Smiles.

By understanding these facts and implementing these strategies, you empower yourself to make well-informed decisions, avoid costly mistakes, and confidently secure your dream retirement home in Thailand.

Legal Disclaimer: The information provided in this article, “Buying Property in Thailand for Retirement: 2025 Legal Guide” is for educational and informational purposes only. It is not intended as, and should not be construed as, legal advice. The laws, regulations, and procedures regarding property ownership in Thailand are complex and subject to change. The content of this article is based on information available as of its publication date and may not reflect the most current legal developments. No professional-client relationship is formed by reading this article. You should not act or refrain from acting based on the information contained herein without first seeking professional legal counsel from a qualified, independent Thai lawyer who is licensed to practice in Thailand and can advise you on your specific situation. New Asia Living and its authors assume no liability for any actions taken or not taken based on the contents of this article.